The New York Times//The New Buzzword That’s Scaring China

BY BOB DAVIS

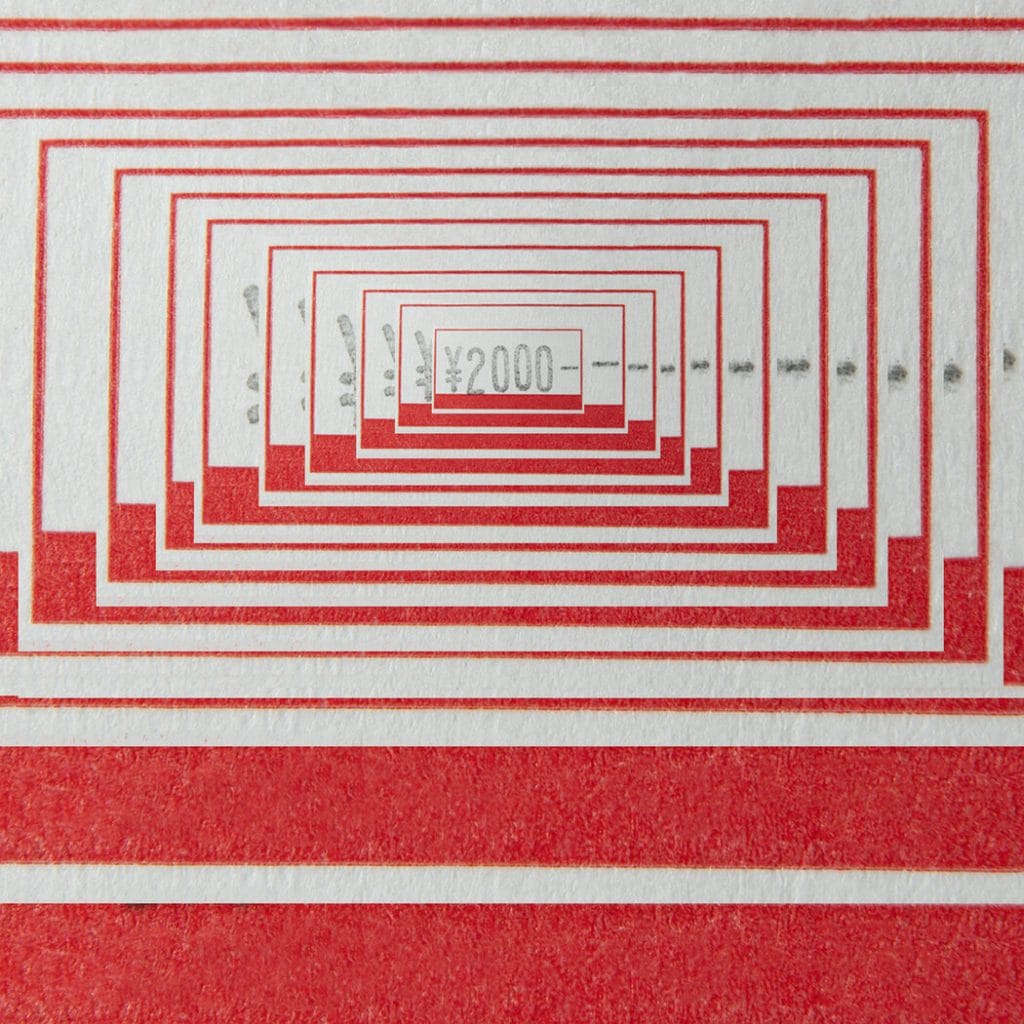

Competition in China is often far more cutthroat than in the United States. America has a handful of carmakers; China has more than 100 electric vehicle makers struggling for market share. China has so many solar panel makers that they produce 50 percent more than global demand. About 100 Chinese lithium battery producers churn out 25 percent more batteries than anyone wants to buy.

This forces Chinese manufacturers to innovate, but it also leads to price wars, losses and bad debt — and that’s becoming a problem.

China is heading toward deflation, the often catastrophic downward spiral of prices that sank Japan in the 1990s. Its leaders are blaming a culprit they call “involution” (“neijuan” in Mandarin), a term that has come to mean reckless domestic competition. They want to rein it in by browbeating companies into keeping prices steady and instructing local governments to scale back subsidies.

It won’t work. At best, those are temporary fixes for China’s more fundamental problem. Its economy relies so heavily on investment for growth, rather than consumer spending, that it produces enormous surpluses that wreck profits at home and provoke trade wars abroad.

China’s infatuation with the term involution dates to the 1960s and the work of an American anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, who argued that Indonesia wasn’t able to feed itself because population growth had outpaced improvements in agricultural productivity. Geertz used involution — an anthropological term for a culture that fails to adapt and grow — to describe this doom loop. His analysis resonated in a China that at the time was struggling to feed its own people, the world’s largest population.

The term gained traction in China during the pandemic, when young people used involution to describe the pressure they felt to get ahead in a stagnant economy. In 2020, a video went viral of a Tsinghua University student peddling his bike at night while working on a laptop propped on his handlebars. Posts related to involution were viewed more than one billion times by the following year.

Initially, older Chinese commentators dismissed this notion of involution, calling it a symptom of Western capitalism. Then, in 2024, Chinese manufacturers gushed red ink and exported goods they couldn’t sell at home at prices so low that America and Europe erected tariffs to bar them. The problem, Chinese officials argued, wasn’t the Chinese economic system. The problem was ruinous, or involuted, domestic competition. In July 2024, the ruling Politburo for the first time identified fighting involution as a priority. Five months later, a government-Communist Party economic conference pledged to “comprehensively address involution competition.”

This framing matters to Beijing, which has been criticized by the United States and Europe as exporting its manufacturing surplus at prices that bankrupt Western competitors. By repackaging its efforts as fighting involution rather than excess capacity, Beijing can argue it isn’t caving in to Western pressure, which a Chinese Embassy spokesman described as “naked economic coercion and bullying.”

In the United States, markets work out any oversupply through production cutbacks, withdrawal of credit and bankruptcies. China relies instead on government and party control. Turning to their old handbook, regulators have called in carmakers, bankers, cement producers and e-commerce platforms, among others, to warn against excessive price cutting. Officials are planning to create a polysilicon cartel to try to ease solar power price wars, and are revising price regulation to guard against what the state-owned Global Times calls “rat-race style” competition. Beijing is also signaling to local government officials they shouldn’t throw lifelines to money-losing local firms — a major shift in a longstanding economic policy on which many political careers have been built.

These kinds of interventions are almost always short-lived. In July, China’s investment spending plummeted, which the market research firm Gavekal Dragonomics argues could be the result of the anti-involution drive. Should that continue indefinitely, the economy would crater. The government would surely ease off before then.

Longstanding policies that encourage excess supply remain untouched. Local officials are still measured by how well the economy grows and how quiescent their citizenry remains. That, in turn, means keeping local companies afloat to ensure the steady availability of jobs and tax revenue.

About a decade ago, Beijing opened a similar campaign to reduce the vast oversupply of steel. Steel mills made a big show of taking furnaces out of production, sometimes blowing them up for TV news. The mills chosen were often obsolete and local governments continued to subsidize construction of more modern facilities. Steel production rose, as did U.S. tariffs to curb steel imports.

What China needs, more than political campaigns, is more domestic spending, which in turn would gobble up more of the excess supply. Western officials and some Chinese economists have made this recommendation for years, but China has resisted. Private consumption accounts for about 40 percent of China’s gross domestic product, compared to about 69 percent in the United States and 53 percent in manufacturing-heavy Germany. That’s in part because Chinese households save heavily to compensate for a skimpy social safety net.

There is no shortage of suggestions on how to stimulate Chinese consumer spending, ranging from income tax cuts to increasing pensions and health care coverage to selling off locally owned companies and awarding shares to every person in the province.

So far, there have been only modest additions to the safety net, and Beijing is wary of reducing the state’s control over the economy and handing it instead to consumers. There is little reason to think this will change. China is likely to try to muddle through its anti-involution campaign hoping that importers, even the tariff-heavy United States, will swallow its excess goods.

That may no longer be good enough to power growth. The risk is that China follows Japan into a period of stagnation from which there is no easy exit.

###

- VIA: The New York Times

- Origianl URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/23/opinion/china-economy-deflation-neijuan.html